What You Should Know:

– A new report from the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) examines the complex and often fragmented regulatory landscape for health AI tools that fall outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). As AI becomes increasingly embedded in healthcare—automating administrative tasks, guiding clinical decisions, and powering consumer wellness apps—these tools operate within a patchwork of federal rules, state laws, and voluntary industry standards.

– The issue brief outlines the types of health AI that are not regulated as medical devices, the key federal and state bodies providing oversight, and the challenges and opportunities this creates for responsible innovation.

While AI tools designed to diagnose, prevent, or treat disease are regulated by the FDA as medical devices, a large and growing category of health AI operates outside of this formal oversight. These tools are instead governed by a mix of policies from agencies like the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and various state authorities.

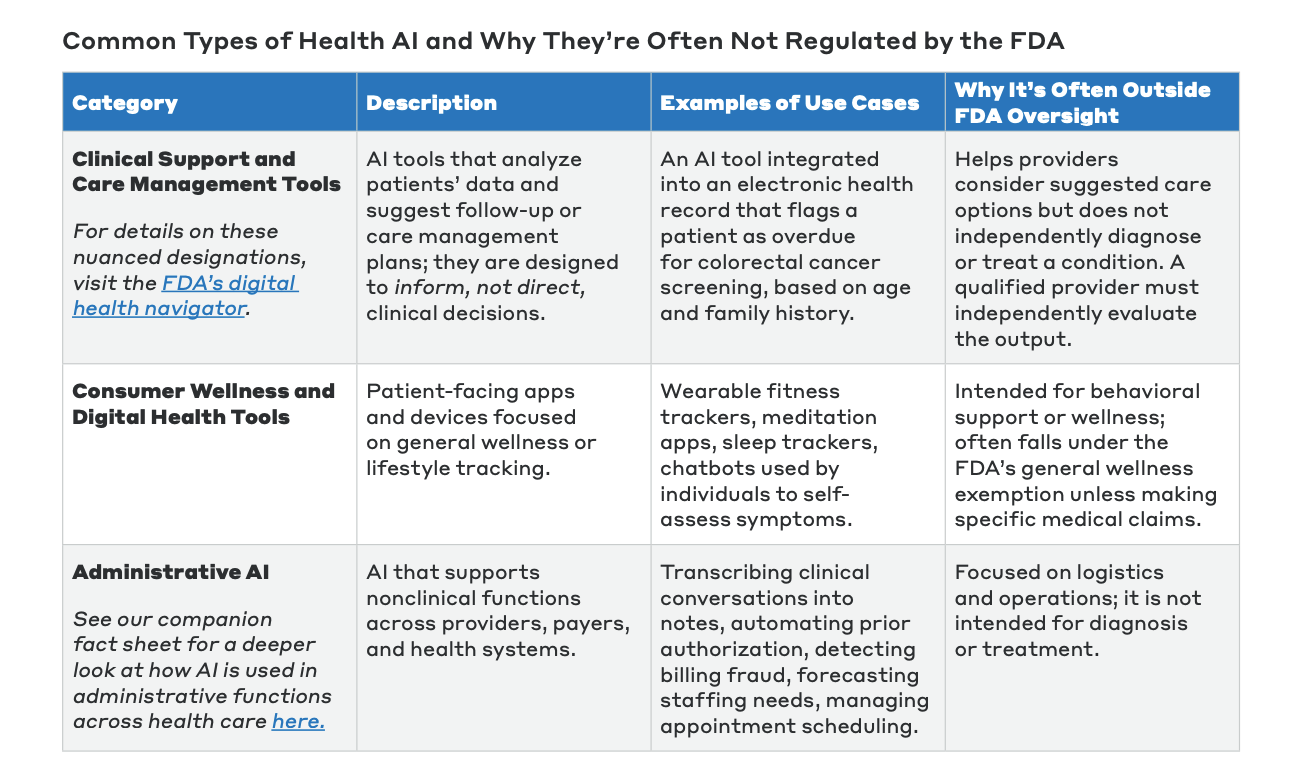

Common categories of health AI not typically regulated by the FDA include:

- Administrative AI: Tools that support non-clinical functions such as automating prior authorization, detecting billing fraud, forecasting staffing needs, or managing appointment scheduling.

- Clinical Support and Care Management Tools: AI integrated into EHRs that analyze patient data to suggest follow-up actions, such as flagging a patient as overdue for a cancer screening. These tools are designed to inform, not replace, a clinician’s judgment.

- Consumer Wellness and Digital Health Tools: Patient-facing apps and devices focused on general wellness, such as fitness trackers, meditation apps, and sleep trackers.

How the 21st Century Cures Act Shapes AI Oversight

The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 was pivotal in defining the FDA’s authority over health software. It clarified that certain clinical decision support (CDS) tools are exempt from being classified as medical devices if they meet four specific criteria:

- They do not analyze images or signals (like X-rays or heart rates).

- They use existing medical information from the patient record.

- They support, but do not replace, the final clinical decision.

- Their recommendations can be independently reviewed and understood by the provider.

If a tool fails even one of these criteria, it may be considered Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and fall under FDA oversight. This creates a significant “gray area” that can be challenging for developers to navigate.

For AI tools that are not considered medical devices, oversight is distributed across multiple federal and state agencies, which can create both flexibility and potential gaps.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC): If an AI tool is integrated into a certified EHR, ONC’s rules require developers to disclose the tool’s intended use, logic, and data inputs. However, this only applies to tools supplied by the EHR developer, not third-party or internally developed apps.

- Office for Civil Rights (OCR): Any tool that handles Protected Health Information (PHI) falls under OCR’s enforcement of HIPAA. OCR also enforces rules against algorithmic discrimination in federally funded health programs.

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC): The FTC can take action against companies for deceptive marketing claims about their AI tools. It also enforces the Health Breach Notification Rule for non-HIPAA-covered apps, requiring them to notify users of a data breach.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS): CMS can influence the adoption of AI tools through its reimbursement policies and Conditions of Participation for providers.

- State-Level Oversight: States are increasingly active in regulating AI. This has led to a variety of approaches, from comprehensive AI risk laws like the one passed in Colorado, to targeted disclosure and consumer protection laws in states like Illinois and Utah. Some states are also creating “regulatory sandboxes” to encourage innovation under defined safeguards.

Ensuring More Defined Frameworks to Support Responsbile AI

The BPC report concludes that the current fragmented landscape creates uncertainty for developers, complicates adoption for providers, and leaves gaps in patient protection. As the industry moves forward, policymakers and industry leaders must continue to collaborate on developing clear frameworks and shared standards to support responsible innovation, ensure patient trust, and improve the quality of care.

“The health care AI revolution is well underway, transforming how care is delivered and raising new questions about regulation. As policymakers and agencies work to balance responsible innovation with patient protection, a clear view of today’s regulatory landscape is essential. This issue brief offers a snapshot to help ground the policy conversations ahead,” said Jonathan Burks, BPC’s Executive Vice President of Economic and Health Policy.